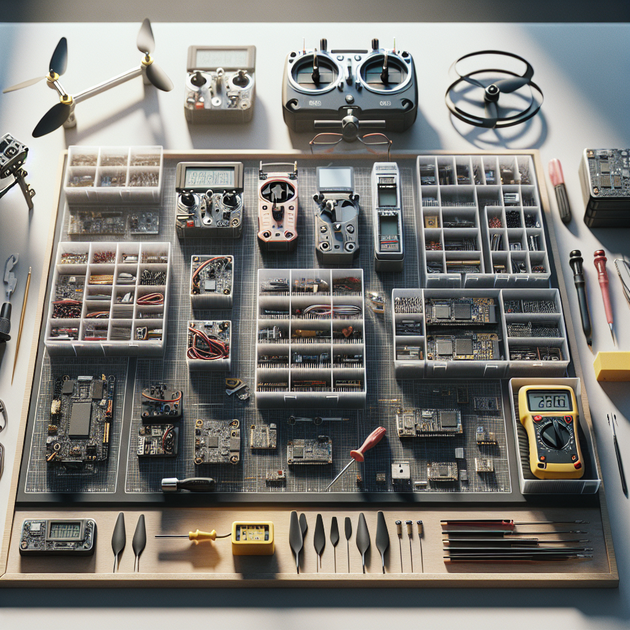

Right now is the perfect time to sort through that growing drone parts collection sitting on your bench. With component prices dropping and open-source flight software maturing fast, you can turn that pile of props, ESCs, and frames into something that actually flies within the next hour—if you organize it right.

Why Your Drone Parts Collection Deserves Attention

Over the last year, new firmware releases for open hardware like Betaflight 4.5 and Ardupilot 4.4 changed what “compatible” really means. Old flight controllers might still work fine—but only if you flash them carefully and match the right receiver protocols. The Reddit post from user GlitteringInjury6863 nailed it with one question: what do you think of this collection? It’s not just about having the gear; it’s about knowing which pieces play nicely together now.

The shift matters because hobbyists often rely on leftover parts from previous builds. A once-top-tier ESC may choke on newer PWM update rates. That’s why checking every part before wiring anything saves you hours of rework later.

How a Drone Parts Collection Fits Together

Here’s the cleanest way I’ve found to evaluate a mixed batch of components before committing solder:

- Step 1: Label each component bag with model and version numbers—use painter’s tape and a Sharpie. Example: “F405 V3 / BLHeli_32 45A.”

- Step 2: Plug each ESC into USB via a signal tester or FC passthrough mode; run BLHeliSuite32, click “Read Setup,” confirm firmware loads without errors.

- Step 3: Connect your flight controller to Betaflight Configurator. Under “Ports,” check UART assignments; note which port handles Serial RX.

- Step 4: Temporarily power your receiver with 5V; verify binding LED behavior matches your transmitter protocol (e.g., ExpressLRS or FrSky D16).

- Step 5: Dry-fit motors on the frame corners; spin each manually—listen for rough bearings or off-balance magnets before locking them down.

If any step throws an error or odd noise, stop there. Mixing brands across generations sometimes triggers timing mismatches that look like software bugs but are actually electrical noise issues. Keep notes per component in a simple spreadsheet—it becomes gold when troubleshooting later.

The Real-Life Test Bench Story

A friend of mine—let’s call him Dan—thought he’d scored big on a used lot of FPV gear from an online marketplace. Twelve motors, four ESCs, two F7 boards, and a random assortment of props for half retail price. He plugged everything in one Saturday morning expecting quick success.

An hour later his bench smelled faintly like ozone. One ESC flashed red then quit entirely; another refused to calibrate throttle endpoints. Dan ended up spending more time diagnosing what was dead than flying anything at all.

The fix came when he sorted everything by protocol first instead of by physical fit. Once he matched his BLHeli_32 ESCs with an F7 board that supported DShot600 out of the box—and ditched the outdated SimonK units—the setup worked flawlessly. Lesson learned: organization beats enthusiasm every time.

The Hidden Trade-Offs in Any Drone Parts Collection

The contrarian truth here is that too much choice can stall your build more than too little gear ever will. Builders often hoard spare components “just in case,” but firmware support ages fast. A five-year-old FC might boot fine yet refuse telemetry sync with modern receivers. That’s not user error—it’s firmware drift.

The safe compromise is to maintain one active set (parts verified with current firmware) and one backup bin (older but known-good). Rotate inventory quarterly—flash everything once even if you don’t fly it yet. That keeps firmware dependencies visible before they bite you mid-project.

If your ESCs or FCs use proprietary configuration apps no longer updated by their vendors, export settings now while the app still runs on your OS version. Store configs as plain text files so they’re readable without legacy tools later.

Quick Wins for Smarter Organization

- Create folders per build type (“Cinewhoop,” “Long Range,” “Freestyle”). Store config dumps inside each folder.

- Mark all cables shorter than 10 cm with heat-shrink color codes—red for signal-only lines avoids confusion later.

- Add small QR stickers linking to datasheets; scan before soldering instead of hunting manuals mid-build.

- Use one dedicated LiPo pack as a testing power source—never grab random charged packs lying around.

- Run a one-minute smoke stop check after any first power-up using an inline current limiter or bulb tester.

Troubleshooting Gotchas Before First Flight

You’ll hit minor snags even after careful sorting. The most common pitfall I see is reversed motor order after flashing new firmware defaults. Always verify motor mapping under “Motors” tab in Betaflight Configurator—spin each motor individually while holding the frame firmly (props off!). If directions are wrong, use the “Resource Remap” feature instead of resoldering wires; it’s faster and reversible.

Another gotcha: USB drivers conflicting between configurators (like iNav vs Betaflight). Uninstall duplicates via Device Manager → “Ports (COM & LPT)” → right-click → Uninstall Device → check “Delete driver software.” Then reconnect only the target FC so Windows assigns a fresh COM port number.

If telemetry data vanishes mid-flight testing in simulator mode, try lowering baud rate on SmartPort or CRSF links by one step; interference sometimes spikes above 400 kbit/s indoors near Wi-Fi routers.

A Sanity Check Before You Commit Solder

You’ve confirmed firmware compatibility and basic electrical health—now perform one final paper exercise before heating up irons:

Sketch a wiring diagram showing every 5V feed path and ground return line. Use colored pencils if needed; visualizing loops exposes hidden risks like shared grounds causing brownouts under throttle bursts. Cross-check pinouts against real silkscreen labels on hardware—not PDF diagrams that may be for earlier revisions.

This ten-minute sanity check prevents some of the ugliest intermittent faults later (random reboots mid-flight). Builders skip it because it feels redundant; experienced ones know it’s insurance worth paying up front.

The Deeper Insight Nobody Mentions

Most guides tell you to buy name-brand parts for reliability—but mixing quality clones with genuine components can actually teach better fault isolation skills early on. As long as voltage specs match and you test systematically, it’s fine experimentation territory.

I’ve seen budget builders who learned faster precisely because they had to debug inconsistent clone hardware; they became fluent in reading serial logs instead of guessing blindly. So yes—cheap parts slow first builds but accelerate learning curve dramatically if approached methodically.

Your Hourly Plan Summed Up

If you’ve got an afternoon free:

- Gather every loose component onto one surface; separate by category (motors, ESCs, FCs).

- Label and document firmware versions immediately after connecting each piece once.

- Create two folders on your desktop: “Verified” and “Needs Flash.” Move screenshots accordingly.

- Toss duplicate micro-USB cables—bad ones cause half of connection headaches anyway.

- End session by charging exactly one test LiPo to storage voltage ready for tomorrow’s dry-run assembly.

A Final Reflection

A well-tuned bench is quieter than any finished quad screaming through the air—it hums with potential energy waiting for its first arm switch flick. What story will your next build tell once those labeled bags become a single humming craft?

Leave a Reply